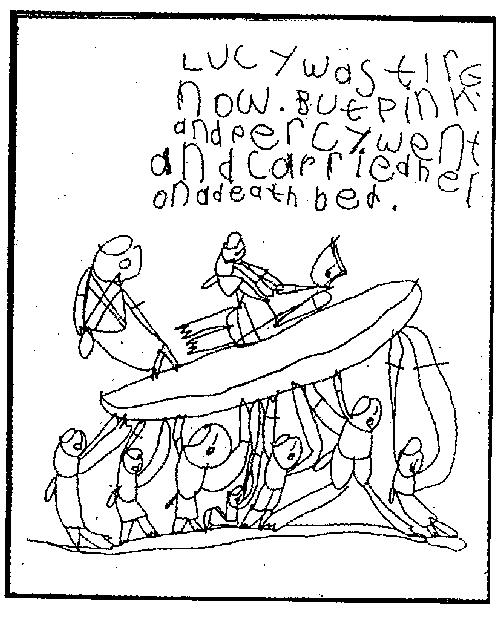

Apocalyptic Vision, Stefan, age 12

DRAWING FOR A PEACEFUL WORLD: NOTES FOR DISCUSSION

Apocalyptic Vision, Stefan, age 12

|

On a winter evening in Vancouver not so long ago a number of teen-aged boys were walking home from a community centre . Suddenly they were confronted by a gang from a different ethnic background. An ugly exchange followed. Badly outnumbered, the boys who had been walking home fled, but one was caught and beaten to death. |

* Whether violence is defined as war or clashes between ethnic groups or teen-gang aggression or bullying at school or outbursts of sibling rivalry, the causes are multiple and complex and beyond the scope of this essay. In contrast, the Drawing Network contribution to the public forum may seem simplistic. Nevertheless, to provide a framework for discussion, here are four propositions to consider:

1) language is at the core of every child's mental development and emotional health

2) spontaneous drawing, as children practice it in the preschool years and beyond, is an un-coded, easy-to-use language, a gift of nature, not of culture

3) spontaneous drawing is grossly neglected in the home/school curriculum

4) anti-social behavior may well be related to this neglect

* If these propositions are valid - as they appear to be - we must wonder what happens to the personal psychology of children and, by extension, to the overall social fabric when children are denied an un-coded, naturally programmed language in the most critical years of their mental development?

IS SPONTANEOUS DRAWING TRULY A LANGUAGE MEDIUM?

* Think of the parallels: in the second year of life children respond to drawing materials by scribbling which is roughly equivalent to babbling or vocalizing. After a period of exploratory mark-making, a familiar object may be recognized within the scribble and pointed to. With or without this moment of recognition, a transition to drawing intentional representations is set in motion and these become a personal graphic vocabulary. (Although drawing is not a product of culture, we can 'read' them as though they were because the biological constants are more or less shared by all. For example, first representations of humans is typically a head/body circle with extended limbs.) This vocabulary of shapes consists of symbolic representations, or schemata, for humans, animals, buildings, natural phenomena, man-made objects, and so on. Schemata are invented as they are needed. In the next stage schemata are combined as meaningful and emotionally charged pictures, some simple and direct, others incredibly subtle and complex. Telling stories with drawings is roughly equivalent to creating sentences, paragraphs, stories and so on with words. The mental processes are roughly the same. Thus, basic units in both languages combine to articulate, express and communicate descriptions, emotional reactions, intellectual propositions and imaginative narratives. We conclude that neglecting drawing in the home/school curriculum denies children a large part of their language heritage!

* There is a major difference between the two languages which gives drawing an advantage in the early years: literacy is a language of codes passed on by a culture and requires years of teaching plus formal and informal learning. It is rarely used spontaneously except for immediate communication. On the other hand, drawing is uncoded and ready to serve the child's immediate psychological needs.

* Children acquire drawing skills not through being taught but through thematic motivation and daily practice. Once the practice of drawing is established, the urgency of experience is sometimes all that is required, but a 'daily draw' benefits from the ongoing involvement of a parent or teacher. The adult role is to discuss possible subjects for drawing and to grant children the freedom to respond or not respond as they choose. It is these discussions, of course, that contribute to literacy and parent/child bonding.

* In spite of a popular misconception, drawing is not restricted to children gifted with a special talent: indeed, every drawing by every child is a language artifact and contributes something to mental development. Moreover, some drawings radiate the qualities we find in mature works of art (for which we have coined the phrase, 'aesthetic energy') and some are so perfectly integrated in form and content that we think of them as authentic 'works of art'. This aesthetic dimension may prove to be the key to achieving and maintaining psychological well-being. We think that the integrated forms that produce 'aesthetic energy' contribute to an integrated personality, to good citizenship and, eventually to a more peaceful world.

* In this paper our focus is on the causes of youth violence and the possible link to language. Consider the challenges faced by some children in the daily grind of schooling. For them the intense teaching and learning associated with literacy is a boring struggle, an occasion for feeling embarrassment and inadequacy, and it seems to go on and on daily through the years and to be a permanent fixture. This frustration may have a double cause: being required to perform poorly in public in front of one's friends and having no means to articulate the subtle and complex thoughts and feelings all children experience growing up. (Of course, children would be unaware of this but would be affected by it.) We don't know the numbers. Is it all children most of the time? A few children some of the time? A minority with special needs? An even smaller minority with 'behavioral problems'? We don't know the broad picture, but every teacher knows from the behavior of her code-challenged children.

* Teaching strategies have improved since I first observed this negative attitude in the small town multi-grade school I attended as a boy. I was one of the lucky ones. My parents read to us without fail at bedtime and I knew that I had to master books as soon as possible. My positive response to literacy promoted an equally positive response towards school. Should it not be so for all children? And my parents encouraged us to draw although they were unaware that drawing is the child's first language. There was no such thing as 'child art' or 'drawing-as-language' in those days.

* Some of my classmates hated all forms of literacy, disliked school, could hardly wait for summer holidays. The 'I hate school' kids were probably more numerous than they would be today when it is likely to be limited to social misfits, 'slow learners', and real or potential bullies, but aren't these the very children we want to help?

* In contrast to the slow readers I remember, the incoherent speakers (except on the playground) and the frustrated writers, here's a quote from Karen Ehrenholz that came in the email today as I was writing this report. Karen is a Drawing Network supporter who teaches through the internet. She comments on a visit to her clients:

'The grade 1 to grade 4 students talked to me about their drawings, using very mature and detailed language to paint a 'picture' of their journal entries. And other students, too, were creating intricate and detailed drawings to illustrate stories from their imagination - these were mainly boys in grades K to 6.'

* We have found that teaching children literacy in close company with spontaneous drawing makes learning literacy very much more pleasant and easier to acquire. Perhaps it is time to formalize a pedagogy of three languages: words alone without drawing; drawing alone without words; and words and drawings together as an integrated language expression. We could think of this last option as illustrating written stories, and writing commentaries on drawings.

IS DRAWING NEGLECTED IN THE HOME/SCHOOL CURRICULUM? WHAT IS YOUR IMPRESSION?

We believe that the situation Karen Ehrenholz describes is increasingly typical of modern school practice but there may be some distance to go in establishing drawing as a standard part of the home/school curriculum. In the absence of research I can only offer impressions based on my years in the field as a UBC student teacher superviser and 20 years contacting parents and teachers on behalf of the Drawing Network. These impressions are not so important if our goal is to reach the parents of individual children, but they are very important if our goal is achieving a critical mass of parents, teachers, academics, and administrators who will work to bring about a needed reform in home/school language education. Here, at any rate, is how it appears to me:

1) PRESCHOOL: Nothing less than a ''daily draw' in all homes with children will build the critical mass needed 'to make a difference to the statistics of violence but, of course, it can only happen one child at a time. And yet our informed guess is that spontaneous drawing in homes with young children is rare. Most parents encourage drawing or at least accept it with benign tolerance, but a 'daily draw' requires more than tacit approval. Without the involvement of a parent, drawing remains a casual pastime. The three years prior to kindergarten/primary are particularly important developmentally but appear to be the very years when the 'daily draw' is most unlikely to happen.

2) KINDERGARTEN/PRIMARY: Drawing as part of a language curriculum is strongest in these years largely because of the professional training of teachers. It may be used mostly as an aid to literacy, less for optimal mental development. The downside is that the gains from drawing in the morning are often compromised by spurious art activities in the afternoon.

3) INTERMEDIATE/MIDDLE SCHOOL AND BEYOND: Drawing appears to be underused in these years even though it has much to contribute to all forms of literacy. It still has the power to build intellect, heal injured psyches, promote humanistic values. The Drawing Network position is that drawing-as-language should be an option whenever it contributes to learning. This is most applicable in four curriculum areas: language arts, science, social studies, and the visual arts. If this ties drawing down too much to curriculum subjects we recommend a free drawing period every day or so to provide a medium for personal expression.

EMPATHY IN SCHOOLING: IS IT THE KEY TO DIMINISHING VIOLENCE?

* In the early days of the Drawing Network I searched psychology textbooks for references to empathy. The few I found were only a line or two in length. It was no big deal twenty years ago but tody there is a strong movement with many internet citations. I recently searched again, this time through the internet, for references to drawing as a source. I came up empty handed. This is puzzling because every time a child draws he or she experiences empathy!

* Empathy as it is used in this essay became a useful term in adult art education in the mid-20th C. Faced with a model in life class, students were (and still are) urged to reach out to 'touch' it perceptually while transferring this experience to paper with a drawing tool. I have found it helpful to explain this as 'going on automatic pilot'. Translated into the mind-functions of psychology, drawing (with empathy) is neither a conscious nor an unconscious act but something in-between which Freud and others have termed the preconscious. (I use the roughly equivalent term, intuition.) It is a familiar feeling for practicing artists in all media and those who teach children recognize it as exactly what they appear to be experiencing when they are absorbed in the drawing process. It will help us appreciate how children feel when they draw if we know that their obvious identification with subject matter is the experience of 'empathy'. It is the feeling of 'at-onement and it is the rationale for healing through art'. To be effective it must be as near daily as possible. Empathy is associated with all the arts and that is why they are all important: drawing simply has the advantage of being the most specific and individual life-focused of all.

* Empathy, growing stronger thanks to a daily regime, boosts self-confidence, promotes family solidarity, helps children make and keep friends, leads to a healthy participation in school and community affairs, contributes to an expansive humanistic point-of-view. It has its beginning with the new-born baby at the mother's breast and expands from there. Many children and, we expect, especially those &nsp;who are prone to anti-social behavior, either have never had an opportunity to develop it, or have lost it along the stress-filled path of growing up. A regime of drawing is recommended, partly for the empathic act itself, partly for the discussions on either end which not only create a much needed bonding with parent or teacher but also provide opportunities to explore the negative forces behind the anti-social manifestation. Children talk more openly about their problems if there is a drawing to refer to.

* There are other ways to experience empathy: being caught-up in a physical game, acting in a play, playing or listening to music, playing house, caring for a child, playing cars, even playing war. But drawing is the way children experience empathy in the widest possible range of perceptual, intellectual and emotional situations and, as we have pointed out, it is denied most children. (Note the diversity of themes in our website drawings, each a product of empathy.)

* For children who draw, empathy reaches a peak of intensity in the fourth, fifth, and sixth years of life and then drops off. These are the critical years when the healing power of 'aesthetic energy' appears to be most readily available. I have studied children's drawings most of my life and as an artist have applied similar criteria to the ones I use in my own critical analysis. This is not so much to seek a relative value - clearly, a child's drawing is not on the same level as serious adult art - but rather to satisfy myself that 'aesthetic energy' does flow, that the drawing is indeed 'a work of art' and functions in the child's mind as such. Children's drawings confirm that making art and responding to it is basic to human psychology. Again we ask ourselves: what happens to the psychology of individuals when an activity so basic is ignored and what happens to a society that fails to see the relationship of this to social harmony.

* Why does 'aesthetic energy' gradually lessen in intensity in the years beyond seven? We know that children begin to move along a developmental path towards a more powerful intellect, towards reason, and the urge to subject life to rational analysis. The goal for parents and teachers is to help children find a balance of empathic synthesis and rational analysis.

* It will be helpful to consider how empathy manifests itself in the drawings of one child, Joanne (6) whose 'Lucy was tired now...' is reproduced here. In a series of twenty-one drawings we get to know the fictional character Lucy and Joanne herself as there is no doubt that they are the same, although Joanne might not have been aware of it. We also get to know her friends and her summer amusement which is leading her gang of friends in a house painting spree!

* One aspect of empathy is its close relationship to a sense of imaginary 'touch'; we feel the inner-body tensions of the characters. Note the fourteen arms supporting Lucy's 'death bed', the splayed legs, the tension Percy is experiencing as he gently lowers Lucy, and Lucy's head not quite touching the slab. We feel the stretch and pull of Percy's arms holding one of Lucy's and feel a sympathetic tension in our own arms. Empathy creates a fusion of two senses, sight and touch, vision and tactility. This is why we have settled on 'empathic realism' as the goal children seem to be striving for in their drawings.

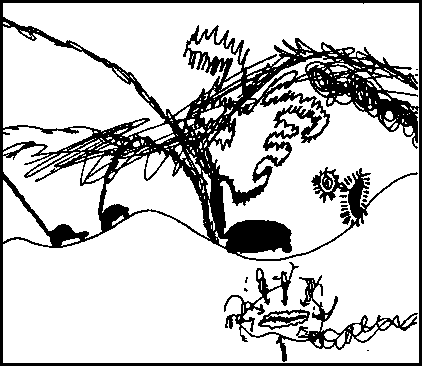

'You I'm going to kill', reads the text of this vicious little drawing which is both mean and self-aggrandizing. If this or similar themes of violence persist, an alert parent or teacher might decide to seek professional help. If spontaneous drawing has not been a daily experience perhaps it is time for a therapeutic regime. Drawings from such a series would be the focus of kindly conversation. When you consider the easy access children have to adult television and the computer games they are allowed to play, it is little wonder that some are encouraged to repeat these violent scenarios in real life.

* Over the years hundreds of drawings have told me that empathy is a process of integration and synthesis. If there is holistic integration in a drawing, how could it happen without something parallel being in the mind of the drawer. Compare the feeling of integration in the two drawings reproduced here: 'Lucy was tired now ...' and 'You I'm going to kill'. The placement of each line in 'Lucy' is simply breath taking while the forms in 'You I'm going to kill' are rigid and mechanical, placed on the paper in a singular lack of integration.

* You may be nervous that drawing will become compulsive and result in a withdrawn child losing touch with reality. Introverted children may indeed find drawing an escape from life but empathy is just as likely to lead to an expanded reality because it takes the child to the peak of his or her potential in three mental categories: perception (how we see things), thought (how we think about things) and feeling (how we feel about things). According to his mother, six-year-old Zion arrived at a large family picnic in his uncle's power launch. On landing he asked for his drawing materials and finding a quiet place, spent ten minutes drawing the boat trip he had just experienced. Only then did he join his cousins at play. Zion's balanced approach is what we want for all children.

DO DAVID'S DRAWINGS TELL US ANYTHING HELPFUL?

* I have been in a position to study one boy's drawings in depth. Our son David went through all the preliminary stages, typically working on the floor with a crayon or colored felts. He was a drawer of battle scenes from an early age and I include a typical example. A sure sign of empathy, he became completely absorbed in the subject, so much so that he typically provided a sound track of grinding tanks and various types of loud ordinance. Did his interest in war spring from a streak of buried violence or aggression? It would appear to be otherwise. He was the most peaceable kid on the block, joined his parents in peace marches, and, as an adult, is today something of a pacifist.

* Two drawings are included and perhaps they represent two levels of 'empathic realism', one evoking a sound track, the other silent and mysterious, one a realistic reconstruction of war, the other bordering on the mythic.

Drawing One: 'Battle Scene' by David (6): typical of a large number of war drawings he made, the kind in which sound track and gestural marks happened as a single gesture, a sure sign that the artist had lost himself in the subject and was experiencing empathy. Four armored vehicles move across a hilly base-line. Three fire canons and attract bombardment. A fourth with a caterpillar track is in trouble. (Is the mechanism on this vehicle a radio transmitter?) And what is that mysterious happening in the lower-right quadrant, the focus of arrows and a scribble indicating either an escape route or an arrival from off- stage?

Drawing Two: Three airplanes fly in combat against a wingless serpent which spirals through the air. Each craft has fired a tracer bullet which precisely touches the snake with amazing control for a six-year-old. Two animals and a grounded plane create a sort of base line and the lowest tracer starts an upward spiral with the snake and remaining planes continuing the lift. The pictorial elements divide space in an impressive formal composition and, at the same time, they tell an exciting story. Form and content are one.

SUGGESTIONS FOR A THERAPEUTIC 'DAILY DRAW' REGIMEN

Can drawing help when the need is for therapy and healing? We believe that it can and the best strategy is one of prevention. Start as early in the child's life as possible. And yet drawing can be introduced to older children with behavior problems who have never drawn. It is never too late. The Drawing Network has produced pamphlets that go into strategies in detail. Here I deal with them briefly.

* Depending on the age and level of resistance, simply providing motivation and avoiding any guidance for how to draw may work. Sometimes a few sessions of getting used to the routine are necessary. Be patient and insistent. Most older children will present you with the 'I can't draw' syndrome. Sweep it aside and take the emphasis off correctness and place it on information. And say as many times as is necessary: 'Draw as best you can! but draw. You will get better with practice.'

* With resistant children evoke play theory. 'We are not making a finished drawing, we are playing a game to help you learn strategies for later! Remember how awkward you were when you started to play basketball.'

* 'Here's a game to help you become familiar with empathic/contour line. Small children start drawing by scribbling, often wildly. We will do a more sophisticated scribble and call it a 'meandering serpentine' That's the term an archeologist once gave to the strange marks in early Paleolithic caves. - (Don't worry: kids love big words! Just explain it to them.) They weren't wild scribbles they were made of lines taking a deliberate path and obviously with great care, moving not too fast and not too slow. My guess is they made them without stopping, one continuous line. That's the kind of scribble I want you to make and as you draw, see if you can take a position above the drawing to watch the 'meandering serpentine' grow on the paper without you consciously instructing it. Just let it happen! In other words, let the 'serpentine' draw itself: go on 'automatic pilot'. Watch it from above.'

* Using the same kind of continuous line and the same pace, practice drawing things from your imagination or things you can see or remember. Instead of a serpentine, create graphic images, symbols that means something. Later we will make involved story pictures using this same line. Keep it moving as long as you can before lifting it to start again. Later we will drop continuous line.

* Introduce 'visualization' and 'guided imagery' to pre-drawing motivation. Visualization is 'seeing' and stimulating possible scenarios on the 'inner screen' of the imagination. 'Guided imagery' is the adult in attendance structuring the scenario by providing graphic subject matter, either before drawing commences or as voice-over. Two drawings on the same theme is a good idea: if the first is a playground fight, 'guided imagery' would ask the drawer to 'see' the fight from close-up, perhaps from the vantage point of a tree branch.

* Gently steer the conversation in a direction that might lead to a focus on an edgy but critically important theme. We want children to reveal the depths of their feelings and to get them discussing the motivating factors that lead to anti-social behavior in the first place. A healing conversation may occur before or after the drawing or both. Children find it easier to talk about their problems in the third person if they can refer to a drawing.

* Turn a drawing scribbler or a scrapbook of unlined pages into a journal related to the particular anti-social problem. Have the child fill it with words. drawings and photographs (perhaps turned into photomontages) which can be used to stimulate drawings.

* Finally, would a 'daily draw' have prevented the tragedy recorded at the head of this essay? If all the boys had experienced drawing from age-two and a 'daily draw' had been in place later, we think there's a good chance that the victim might not have lost his life. On the larger issues of war, religious persecution, racism and so on, it will take a huge and rapid drive towards a reform in language education to make a difference. Still, it is a goal worth pursuing because the benefits start immediately. Networking is the mechanism we use and in this we ask for your help. Please contact your circle of friends and colleagues and discuss the contents of this paper. (It was written to aid such discussions.) There's a good chance that our children will benefit and grow-up to be tolerant, integrated human beings. That is what we all want.

Bob Steele, Associate Professor (Emeritus, UBC)